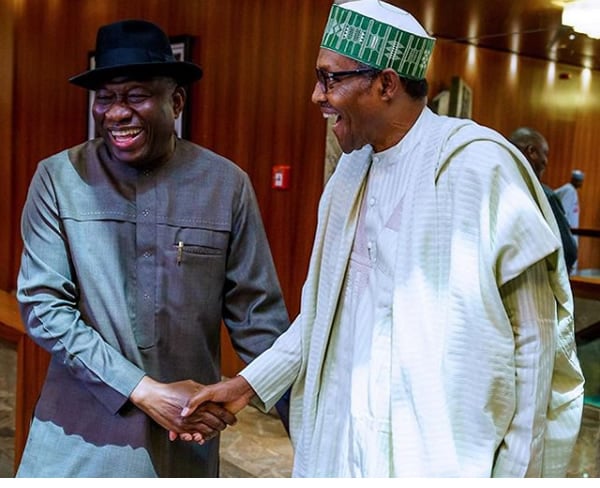

Former President Goodluck Jonathan has revealed that Boko Haram insurgents once nominated his successor, Muhammadu Buhari, to represent them in peace negotiations with the Federal Government.

Jonathan made this disclosure on Friday during the public presentation of Scars, a memoir authored by former Chief of Defence Staff, General Lucky Irabor (retd.), in Abuja.

He explained that his administration established several committees to explore dialogue with the insurgents. At one point, the sect specifically named Buhari as their preferred representative in talks with the government.

According to Jonathan, this development gave him the impression that Buhari, upon assuming office in 2015, would have found it easier to secure the insurgents’ surrender. However, the violence persisted despite expectations.

“One of the committees we set up then informed us that Boko Haram nominated Buhari to lead their team for negotiations,” Jonathan recalled. “So, I felt that when Buhari eventually took over, it would have been easier to negotiate with them. But the insurgency continued.”

The former president noted that Buhari’s inability to end the conflict demonstrated the deep-rooted and complex nature of the Boko Haram crisis.

“Research alone cannot provide the full picture of Boko Haram,” Jonathan said. “I was there. The insurgency began in 2009 while I was vice president. I assumed office in 2010 and spent five years battling it until I left government. I thought Buhari would end it quickly, but today Boko Haram is still with us. The matter is far more complicated than many imagine.”

Jonathan stressed the need for Nigeria to approach the insurgency differently, beyond conventional security tactics, while expressing hope that the country would eventually overcome the menace.

He also urged military officers who were directly involved in operations against Boko Haram to document their experiences for historical clarity.

Reflecting on his administration, Jonathan described the abduction of over 200 Chibok schoolgirls in 2014 as a permanent scar on his presidency.

“It is a scar I will die with,” he said. “But perhaps, one day, more details will emerge, especially if Boko Haram leaders themselves write about their motives, just as key actors of the Nigerian Civil War documented their accounts.”

Jonathan dismissed the notion that Boko Haram’s violence was solely driven by poverty or hunger, stressing that his government adopted multiple strategies that did not succeed.

“If it was just about hunger, we tried different approaches,” he said. “But Boko Haram had access to sophisticated weapons, sometimes even more than our soldiers. That showed external forces were also involved.”

He suggested that a carrot-and-stick approach could be useful in addressing the crisis, but insisted that the advanced weaponry of the sect indicated that its operations were not limited to local grievances.

“Sometimes the ammunition they carried exceeded what our troops had,” he explained. “So where were these weapons coming from? Clearly, there were external hands in the conflict.”

Boko Haram, which originated in Borno State in the early 2000s, grew into a major threat after its founder, Mohammed Yusuf, died in police custody in 2009.

By 2012, reports emerged that the group had nominated Buhari, then an opposition leader, as one of the respected northern figures they trusted to mediate with government. Buhari publicly rejected the offer, accusing the Jonathan administration of attempting to politicize the insurgency.

Jonathan, however, maintained in Abuja that Boko Haram’s preference for Buhari as a negotiator was real, and that the group’s survival until today reflects the complexity of Nigeria’s security challenges.