By Isiaka Mustapha, Editor-In-Chief, People’s Monitor

The Federal Fire Service Act of 1963 is long overdue for a fundamental review. Drafted in a period when Nigeria had fewer urban centres, limited industrial activity, and almost no high-rise culture, the Act has failed to adapt to today’s fire risks and modern realities. Its scope is narrow, outdated, and silent on the most urgent needs of a 21st-century fire service. It does not compel preventive fire safety systems in public buildings, it denies the Service the teeth to sanction defaulters, and it makes no provision for welfare, modern training, or institutional development. In its current form, the law traps the Federal Fire Service in a reactive role rushing to disasters instead of preventing them.

The Act’s greatest weakness is its failure to mandate modern fire safety standards. Nowhere does it require smoke detectors, alarm systems, sprinklers, fire extinguishers, evacuation routes, or drills in schools, hospitals, markets, hotels, banks, offices, or other public places. Without such legal obligations, building owners and managers face no binding duty to prevent fires, leading to needless tragedies. The Lagos Island inferno at a UBA branch, where people leapt from upper floors in desperation because the building lacked suppression systems, remains a grim reminder. Unless the law compels preventive safety as a strict duty, Nigeria will continue to count casualties from avoidable disasters.

Equally alarming is the absence of fire service clearance in the building approval process. In advanced nations, no structure receives occupancy certification without fire safety approval. In Nigeria, however, developers freely erect skyscrapers and commercial complexes without fire input, creating hidden death traps. A reformed law must require fire service approval before construction, and enforce periodic certification to guarantee ongoing safety.

More critically, the law must grant the Federal Fire Service prosecutorial powers. At present, fire officials cannot conduct mandatory inspections, issue compliance orders, or shut unsafe premises with the force of law. Their warnings are often ignored, reducing them to spectators until tragedy strikes. A new Fire and Emergency Services Act must explicitly empower fire officers to inspect facilities, order corrections, seal non-compliant buildings, and prosecute violators of fire safety laws. Gross negligence resulting in loss of life should attract both civil and criminal liability. Without this prosecutorial authority, the Service cannot effectively protect Nigerians, and unsafe practices will persist unchecked.

Beyond infrastructure and enforcement, the welfare of firefighters must be guaranteed. Firefighting is among the world’s most dangerous professions, yet Nigerian firefighters work under perilous conditions with obsolete equipment, poor remuneration, no health or life insurance, and inadequate hazard allowances. The new Act must enshrine welfare provisions: competitive salaries, pension rights, risk allowances, medical insurance, and compensation for injuries or death in the line of duty. These are not benefits but essential protections that reflect the risks firefighters bear daily.

Modern training must also be institutionalised. Fires today involve industrial plants, petroleum depots, hazardous chemicals, high-rise evacuations, and even climate-driven disasters. Nigeria needs firefighters skilled in handling chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats. A reformed law should establish a National Fire Training Institute with regional centres, provide continuous simulation drills, and foster partnerships with international academies to upgrade skills to global standards.

The National Assembly must act decisively. Each day of delay puts lives, livelihoods, and investments at risk. The new Fire and Emergency Services Act must combine preventive safety mandates, prosecutorial powers, personnel welfare, and modern training into one enforceable framework. Anything less would be legislative failure with deadly consequences.

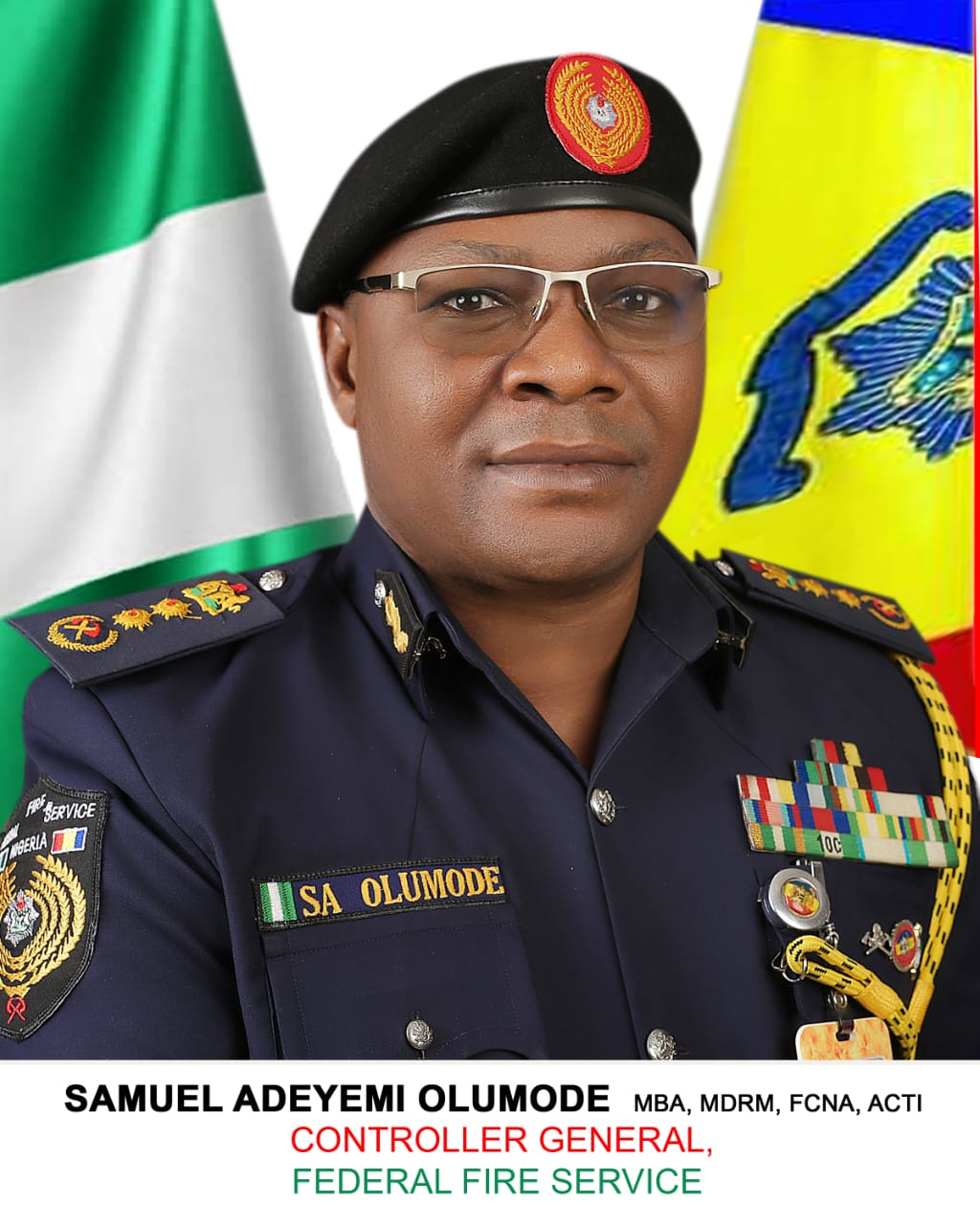

At this critical juncture, the leadership of Controller General Samuel Adeyemi Olumode is pivotal. Nigerians expect him not only to improve operations but to lead the charge for reform. He must champion the amendment of the outdated Act, rally public and institutional support, and press lawmakers to pass a law that equips the Fire Service for modern challenges. His legacy will be defined by whether he secures the prosecutorial authority, enforcement powers, and welfare reforms that Nigeria’s fire service has long been denied.

The reality is undeniable: Nigeria cannot fight twenty-first century fire risks with a law conceived in the mid-twentieth century. The Fire Service Act of 1963 should be archived, replaced by a modern and enforceable framework that saves lives, protects investments, and builds resilience. Any further hesitation is a dangerous gamble with Nigerian lives one the country cannot afford.